|

| Community Writing Center exhibit panels set up in the Sorenson Unity Center lobby |

Yes, there was food.

My husband, daughter and I were welcomed in the lobby/gallery area by a couple members of the CWC staff, Nkenna Onwuzuruoha, and Andrea Malouf. There was a small banquet table with cookies, fruit, and veggies. We grabbed some food, and seated ourselves next to a middle-aged, African American couple. (My husband, daughter, and I are white, by the way). They were friendly, and introduced themselves right away. Betha said she was one of the readers, and that she'd been attending CWC classes and workshops for some time now. I was surprised that I didn't see more black people there for the reading. The Utah Freedom Writers project had advertised with a "Get on the bus!" slogan, clearly invoking the 1960's civil rights era, so I thought the project would have attracted more of Utah's black population. When the event progressed to the auditorium, I glanced around the group, and assessed that 80% or more of the attendees were white. However, as each writer shared his or her story, it became evident that we were widely diverse in our experiences, and in the kind of civil rights messages we wished to convey.

| |

| Sorenson Unity Center Performance Theater |

The auditorium was actually a black box theater. We nearly filled up a seating area of 60-70 new-looking chairs set up on risers. There was a dramatic spotlight pointed down at a miked podium stage-right. And a large projector screen center stage. The ceiling was at least two stories tall.

Things get started

|

| John McCormick |

|

| Ken Verdoia |

Next, we watched a short film entitled, "Even-Handed." It was part of Spyhop's recent project, Navigating Freedom: A Utah Youth Perspective. The film is about a white, straight, teenage girl who keeps a human-rights sticker on her backpack.

She is asked by a peer, "Are you a lesbian?"She then expresses concern for people who feel like they have to hide themselves. She feels that in contrast it's not fair that she has privilege in society.

"No, I'm not."

"Then why do you care?"

Before Nkenna invited the writing project readers to present their writing (the main event), she read a piece of her own. She used water as a metaphor for writing, and suggested that it was a fitting comparison for the occasion because of water's role in 1960's civil rights movement: segregated drinking fountains, and high-pressure water hoses used by police to break up protestors.

And now, the Freedom Writers:

| |

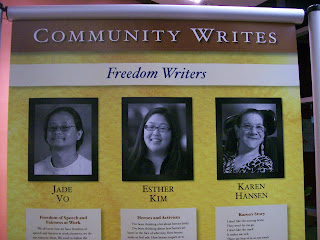

| A few Freedom Writer faces were displayed on CWC exhibit panels in the Sorenson Unity Center lobby. |

A young woman with dark hair and an olive complexion started reading what sounded like a first person narrative of a child in an orphanage. It was entitled, "Forgotten." As the story progressed, it seemed to change like a dream. Was the character really a young orphan, or was he/she an incarcerated adult? The character was taken to "a room that never brings happiness" where he/she was placed on a table. Finally, a few sentences from the conclusion, the details became clear. It was the perspective of a dog being put to sleep. Following her story, the author explained that she was inspired to write this when she learned that an animal rescue shelter she followed on Facebook was being shut down, that the animals would have to die. When I spoke to her after the meeting, she said that her writing wasn't just an animal rights piece, but that she intended it as a metaphor for other civil rights issues as well.

A short woman (white, middle-aged) read a poem she wrote called, "Two Sisters Teach Me Somali." She was a teacher for an English education program. The Somalian women were refugees. The poet was concerned that the stricture of immigration laws makes it hard for people in great need to obtain legal status before coming to the U.S.

Another white woman came to the stand and mentioned being part of a bisexual organization. Her piece was a poem about celebrating the legalization of same-sex marriage in New York, while still feeling the irony of having to "beg for rights / that should already be ours."

Three readings were authored by residents at a living center for persons with mental disabilities. One was read by a friend of the author, another was read by a CWC staff member. But the first was read by the author, herself. She was a woman with what I thought was a rural Utah accent. She had long brown hair, and looked mixed-race to me. She explained that she grew up in an abusive home, was put into foster care. Her mother tried to smother her once with a pillow. "I blame my mom for my learning disability," she said. Then she talked about becoming a mother herself. Her daughter, whom she loved very much, was taken away from her and put up for adoption by the state. It all started when a social worker found a dead mouse in her oven. She didn't understand why it wasn't enough to explain that she had stopped using the oven once she noticed the mouse smell. I wondered if Child Protection Services concluded that she was baking mice and feeding them to her kids.

Tangent!

This is a moral dilemma worth pondering, I thought. On one hand, it's just and merciful for government to step in and take care of children who are believed to be endangered in their own homes. But at what point does the government's interest in protecting the safety of children collide with a parent's right to have custody of his/her own child? I began to imagine a more ideal solution. What would it be like to live in a society where we didn't send people to programs or institutions to be taken care of, a place where extended families lived together, and took care of each other, and where trusted neighbors filled in for those without family support. In this kind of society, people who need extra care (children, the elderly, people with disabilities or psychological conditions, people with serious drug addictions, etc.) would be taken in and cared for daily in their own homes by their own family and friends. If this kind of social structure were more mainstream, perhaps the government would take a regulatory step back. But is my dream-world a realistic possibility for the future, or is it just a re-run episode of The Waltons?

More Freedom Writers:

In one woman's paper, she said she was part of "the omni-sexual collective consciousness." She was concerned that because of her sexual orientation, she feels like she's expected to be invisible where public display of affection is concerned. "I find myself maneuvering to the back of the bus," was her metaphoric allusion to Jim Crow law.

A white man with a white beard spoke about civil disobedience. He talked about converting to Quakerism as a teenager in the '50s. Because Quakers commit to pacificism, his challenge was to stand up for what he believed at a school with a compulsory ROTC program. "I was far luckier than many of the brave protesters against racial discrimination in the South," he said, "I could only be expelled from school for acting on my beliefs, not beaten, jailed, or killed."

A few more CWC members read pieces in behalf of authors who could not attend the meeting, but who wanted their work read. One of these papers took up the subject of prejudice against the homeless, and people with psychological conditions. "Stigmas would categorize me as a weak link in the strength of society. After all, I have admitted to being homeless, depressed, hearing voices, following impressions, and have shown signs of manic creativity. However I will argue that I can make society stronger."

At some point during the readings, I wrote in my notes, "I didn't expect this to be so emotional." One of the most compelling pieces was written by a man with a Spanish name. His work was read by another CWC staff member. She explained that she'd be filling in as a reader, and then said, "I just hope I can do his writing justice." His story was sincerely dramatic, and her voice was equal to the task. He explains that when he was a child, there was a part of him he felt he had to hide because of pressure from family and peers, "I put the 'real' me away . . . in a compartment." He describes his marriage to a woman he really only loved as a best friend. Then, he discretely divulges his regret that love-making with her always felt like a chore. 10 years later, he finally came to terms with being gay, and they were divorced. He greatly regretted the pain he had caused to his wife. He ends the piece by discouraging others like him from making the same mistake, and encouraging society in general to give everyone the freedom to love and be loved. "The wrong match is bondage. The right match is freedom."

How it ended

A few more pieces were read, and Andrea gave some final comments. "Wow--I think I've gone through every possible emotion tonight from goosebumps to sadness to wanting to stand up and shout." I thought I could feel everyone nodding in agreement.

|

| Freedom Writers and CWC staff members lingered to chat after the readings. |

https://bayanlarsitesi.com/

ReplyDeleteEskişehir

Erzincan

Ardahan

Erzurum

NVQV11

van

ReplyDeleteelazığ

bayburt

bilecik

bingöl

P0XQW5

whatsapp görüntülü show

ReplyDeleteücretli.show

S62TUC

görüntülü.show

ReplyDeletewhatsapp ücretli show

NHO

64864

ReplyDeleteAntep Evden Eve Nakliyat

Paribu Güvenilir mi

Mardin Evden Eve Nakliyat

Amasya Evden Eve Nakliyat

Binance Referans Kodu

4CA63

ReplyDeleteÇankırı Evden Eve Nakliyat

Adana Şehirler Arası Nakliyat

Burdur Parça Eşya Taşıma

Kilis Evden Eve Nakliyat

Afyon Evden Eve Nakliyat

Uşak Parça Eşya Taşıma

Çerkezköy Buzdolabı Tamircisi

Ordu Lojistik

Bitget Güvenilir mi

52DD5

ReplyDeleteÜnye Oto Boya

Aydın Lojistik

Mersin Lojistik

Ünye Televizyon Tamircisi

Iğdır Evden Eve Nakliyat

Balıkesir Şehir İçi Nakliyat

İstanbul Evden Eve Nakliyat

Ağrı Parça Eşya Taşıma

Tekirdağ Parça Eşya Taşıma

9D9F3

ReplyDeleteManisa Evden Eve Nakliyat

Bitmex Güvenilir mi

Gümüşhane Lojistik

Tekirdağ Lojistik

Bayburt Parça Eşya Taşıma

Lbank Güvenilir mi

Muğla Şehirler Arası Nakliyat

Aksaray Şehir İçi Nakliyat

Keçiören Parke Ustası

65012

ReplyDeleteen iyi ücretsiz sohbet siteleri

izmir bedava sohbet uygulamaları

aksaray ücretsiz sohbet sitesi

yalova sohbet uygulamaları

aydın canlı sohbet odası

kilis canlı sohbet bedava

bolu mobil sohbet

kilis mobil sohbet odaları

trabzon kızlarla canlı sohbet

00689

ReplyDeleteücretsiz görüntülü sohbet

osmaniye kadınlarla sohbet

bilecik mobil sohbet chat

tokat görüntülü sohbet canlı

Çorum Canlı Sohbet Siteleri Ücretsiz

Istanbul Canli Sohbet Chat

yalova yabancı sohbet

en iyi ücretsiz görüntülü sohbet siteleri

niğde canlı görüntülü sohbet odaları

76711

ReplyDeleteyozgat görüntülü canlı sohbet

sesli görüntülü sohbet

aksaray yabancı görüntülü sohbet

Bolu En İyi Görüntülü Sohbet Uygulaması

kars sohbet chat

siirt telefonda kızlarla sohbet

Burdur En İyi Görüntülü Sohbet Uygulamaları

Konya Sesli Sohbet Odası

canlı sohbet sitesi

E2181

ReplyDeletecanlı sohbet siteleri ücretsiz

ağrı parasız sohbet siteleri

sakarya mobil sesli sohbet

görüntülü sohbet sitesi

artvin telefonda görüntülü sohbet

canlı sohbet et

bitlis görüntülü canlı sohbet

kırıkkale en iyi rastgele görüntülü sohbet

Giresun Telefonda Kadınlarla Sohbet

A59BC

ReplyDeleteKwai Beğeni Satın Al

Onlyfans Beğeni Hilesi

Binance Kaldıraçlı İşlem Nasıl Yapılır

Parasız Görüntülü Sohbet

Raca Coin Hangi Borsada

Twitch İzlenme Satın Al

Tumblr Takipçi Satın Al

Paribu Borsası Güvenilir mi

Binance Referans Kodu

C1CC7

ReplyDeleteBitcoin Kazanma

Referans Kimliği Nedir

Binance Nasıl Oynanır

Coin Nasıl Üretilir

Parasız Görüntülü Sohbet

Tesla Coin Hangi Borsada

Gate io Borsası Güvenilir mi

Jns Coin Hangi Borsada

Soundcloud Takipçi Hilesi

A5F14

ReplyDeleteYıldızeli

Kozluk

Kuluncak

Yenice

Kırşehir

Karşıyaka

Çavdır

Sarıgöl

Sarayönü

5C20B81196

ReplyDeletetiktok ta takipçi kasma

8A0E7D4130

ReplyDeleteinstagram yabancı gerçek takipçi