The Culturalist

Conversations on Utah culture and cultures.

Saturday, May 23, 2015

Mormon Polygamy and my Theater Blog

The study of history is the study of the most peculiar culture of all. For the past few years, I've been focusing my culture-study and sociological coding efforts on a project that keeps this truth ever in the forefront of my mind: from piled stacks of notes and primary source quotations, I've been growing a play about 19th century Mormon Polygamy. Read all about my playwrighting progress on my independent theater blog.

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

colorblind casting

My friend, Mahalia, a wonderful actress who student-taught one of my high school drama classes in Tallahassee, Florida many years ago, recently shared this article on Facebook: 3 Things Actors Should Know About Race on Stage. Mahalia's posting comment suggested that she was sharing the article because of the race-based limitations she faces in her acting career. Here's how she introduced it:

Even when screen writers and playwrights attempt to "take race out" of their stories, or create stories without race at all, this easily lends itself to more race inequality in casting, as the 3 Things Actor Should Know articles explains in the form of a warning to actors, and a little chastisement to directors and writers:

In the facebook discussion below Mahalia's posting of the 3 Things Actors Should Know article, someone commented that a little progress has been made where racial diversity in casting is concerned in New York, in particular, classical Greek and Shakespearean plays are cast with broader racial diversity, including casting members of a family with actors of different races. I've often seen that casting philosophy used in local Shakespeare, and Fairy-Tale themed plays here in Utah. For example, two weeks ago, I attended a Grassroots Shakespeare production outdoors at Salt Lake City's Liberty Park in which a mixed-race man played a romantic lead, Bianca's wealthy suitor, Lucentio. But I think it's easy for directors to make less-traditional casting choices for classical plays, because the stories are so well-known. Whereas, for most post-renaissance pieces, directors prefer casting with historical accuracy and realism in mind. There are many historical or fictional plays in which race is a significant part of character identity or expression of the historical setting. There's also the obligatory logic that says characters in the same biological families should be of the same race. And let's face it, directors are afraid of getting the audience confused about the setting and characters.

Before I cast David as Wilford's brother, I considered my own concern about confusing the audience. My main objective was to teach my audience about some historical events--but I reminded myself that as the author and director I can communicate with the audience any way I want. It was easy, I simply made sure that in the dialogue, David's character was introduced clearly as Wilford's brother, and POOF! disbelief suspended!

As an afterthought, I have to remark to myself that David was one of only 2 actors of color who auditioned. Why were there so few auditioning actors of color? Probably because of the topic of the play. There are many pioneer history plays and film productions here in Utah, and it may be that actors of color commonly don't bother auditioning for shows like that because they suspect all the roles are white.

I would never suggest that out-of-historical-context colorblind casting is right for every production, but I'd love to see it done more often in mainstream theater.

Here's my list of progressive changes I hope to see in the future of theater, film, and television:

I wish that directors did cast with "absence of color". As a black stage actress....I know that I will NEVER be allowed to play Katarina, Maggie the Cat, Glenda, or any other of my dream roles, unless it's an all-black version of the play. Just the simple reality. Color hinders me....but I try and navigate this crazy theatre world nevertheless.Certainly, any actor or actress's work prospects are limited by thousands of talent, personality, and physical characteristic factors, but race is a special and particularly tricky barrier for many actors, because in the U.S. most film, theater, and television productions are white people stories, produced mostly by white people, mostly for white people. Yes, they find ways of adding in racial diversity, but whiteness tends to be the original ingredient.

Even when screen writers and playwrights attempt to "take race out" of their stories, or create stories without race at all, this easily lends itself to more race inequality in casting, as the 3 Things Actor Should Know articles explains in the form of a warning to actors, and a little chastisement to directors and writers:

Absenting characters of color, absents artists of color. Aspiring playwrights and screenwriters are generally taught not to specify the race of their characters—unless a character’s race is consequential to the dramatic narrative. The aim is to create the greatest flexibility in casting and to increase the odds of the work being produced.

Since it’s impossible to imagine a person as being race-less, the default assumption is that most unspecified characters are white. Although producers, directors, and casting agents have discretion in the person who they hire to work on a production, they frequently begin with a script that absents people of color.For the past couple of years, I've been thinking about this topic, especially since, as a playwright in Utah, my current interest is creating works about LDS (Mormon) Pioneer history--there are very few characters of color in that segment of history, and very little written by them or about them. This has been a bit of an internal conflict for me, as I am interested in putting both early LDS Church stories and racial diversity on stage. Last year, while writing the play I produced about Wilford Woodruff, I considered including a scene based on his journal's detailed description of a conversation he had with a Ute chief, but then I realized that it didn't really fit into the rest of the story and that I was only trying to squeeze it in, because I was bothered by the prospect of creating a show with an all-white cast. I decided not to include the scene. But then when I held auditions, I discovered that a friend of mine, David, a Columbian with a dark complexion, was clearly the best actor for the supporting role of Wilford's brother.

In the facebook discussion below Mahalia's posting of the 3 Things Actors Should Know article, someone commented that a little progress has been made where racial diversity in casting is concerned in New York, in particular, classical Greek and Shakespearean plays are cast with broader racial diversity, including casting members of a family with actors of different races. I've often seen that casting philosophy used in local Shakespeare, and Fairy-Tale themed plays here in Utah. For example, two weeks ago, I attended a Grassroots Shakespeare production outdoors at Salt Lake City's Liberty Park in which a mixed-race man played a romantic lead, Bianca's wealthy suitor, Lucentio. But I think it's easy for directors to make less-traditional casting choices for classical plays, because the stories are so well-known. Whereas, for most post-renaissance pieces, directors prefer casting with historical accuracy and realism in mind. There are many historical or fictional plays in which race is a significant part of character identity or expression of the historical setting. There's also the obligatory logic that says characters in the same biological families should be of the same race. And let's face it, directors are afraid of getting the audience confused about the setting and characters.

Before I cast David as Wilford's brother, I considered my own concern about confusing the audience. My main objective was to teach my audience about some historical events--but I reminded myself that as the author and director I can communicate with the audience any way I want. It was easy, I simply made sure that in the dialogue, David's character was introduced clearly as Wilford's brother, and POOF! disbelief suspended!

As an afterthought, I have to remark to myself that David was one of only 2 actors of color who auditioned. Why were there so few auditioning actors of color? Probably because of the topic of the play. There are many pioneer history plays and film productions here in Utah, and it may be that actors of color commonly don't bother auditioning for shows like that because they suspect all the roles are white.

I would never suggest that out-of-historical-context colorblind casting is right for every production, but I'd love to see it done more often in mainstream theater.

Here's my list of progressive changes I hope to see in the future of theater, film, and television:

- more people of color creating scripts,

- more producers using those scripts,

- more producers of color becoming influential leaders in theater and media arts,

- greater variety of racial perspectives represented in stories told on screen and stage no matter who writes it (too often"racial diversity" looks like this: a white protagonist with white-person problems, he or she has one or more "side-kick" friends of color, but they are relatively flat characters.)

- more directors willing to take out-of-historical-context casting risks, and

- fewer directors assuming a character's race is white if race is not mentioned in the script.

Sunday, February 3, 2013

A new perspective on Chinese child-rearing strategies

There were four of us in the car, driving back to Salt Lake City from Summerhays Music store in Murray, Utah. My husband, Justin, was driving, I was in the passenger seat, and in the back were my two-year-old daughter, Lydia, and one of Justin's friends, Sunny. That evening, we were helping Sunny with a little violin shopping.

Here's the socio-cultural backdrop for the scene: Justin and Sunny are both students in the physics graduate program at University of Utah. Justin and I (and Lydia) are white with mostly British heritage, our families have been American for many generations. Sunny and her parents are of Chinese heritage, although she was born and raised in Malaysia. She came to the states on her own last year when she started the graduate program at UU. Her first language is English, which she says is typical for those who grow up in "British-occupied" Malaysia.

We were chatting about Meyer's Brigg's personality types, when Lydia became the topic of conversion. Here's my best attempt at paraphrase:

"You can tell there's something different about her," said Sunny.

"You mean, because she's so extroverted?" I said.

"Well," Sunny continued, "she has a kind of victorian grace, but she let's you know that she's in charge. She reminds me of Queen Elizabeth." People often comment on Lydia's character. She's a friendly, bossy, charming, loud, wide-eyed, unbridled, curious busy-body who happens to say "thank you" when you hand something to her.

Sunny added more, "Lydia really fills up the room." I mentally reflected on how Lydia had just filled a large musical instrument store with all her Lydia-ness. She ran here and there, squealing like a little pig while I chased her, calling, "No, no, no, don't touch the harps!" "Pick up those reeds and put them back, Baby!" "Okay, fine, you can play that piano, but not with your feet, please!"

"Asian babies are much different" Sunny said a moment later. "They are very passive." I immediately tried to think of an exception, but I couldn't.

"I'm going through my head trying to picture the Asian babies I know," I said, "And all of them are like what you're saying, very reserved. Why is that, do you think? I mean, in your opinion, would you say that's genetics or upbringing?"

"It's because of the way they are raised," she replied.

"What do Asian parents do differently?" I asked.

"They purposely disconnect themselves from their children. They don't show affection. They don't interact much with them, even when they are babies. They don't even use baby-talk with them, they speak to them like they're adults." She went into more detail, but this was the essence. I had heard of Asian parents demanding great discipline and excellence from their children, and the strain this must inevitably put on the child-parent relationship, but I had never imagined these scenarios within the context of growing up sans affection, and with limited interaction.

I was overcome by how backward it sounded to me. How can an entire culture of people, generation after generation, live without familial closeness and emotional dependence? The idea was contrary to everything I believe and value about life. I wanted to know what Sunny thought about it.

"When you have children some day," I asked, "do you think you will raise them the same way you were brought up, or will you do it the way Americans do?"

She hesitated, thinking about it, then answered, "I think I will do it the Asian way . . . Yes, I will."

I was surprised, so of course I had to ask (trying to give up my bias), "And why do you want to do it that way? What would you say are the benefits?"

I loved Sunny's response. Without a hint of defensiveness, she replied, "The way my parents raised me taught me independence. Even as a child, I knew that I could take care of myself, that I didn't need them--this was a great gift that they gave me." She also explained that while her parents didn't put an emphasis on closeness, they were not neglectful. "To them, being a good parent was about being responsible, following through on your duty." She spoke of them with consistent admiration.

I asked her if she felt like her parents loved her. She said that the first time she really felt their love, was last year when she was new in the U.S. and was in a situation of desperation. "I just asked for their help, and they were so generous--I couldn't believe it."

I thought of an episode of Glee I had seen in which an student begs his father to accept his choice to become a professional dancer. The student expresses a longing for his father's approval and love. He suddenly becomes aware of his father's disconnectedness, and finds it tragic. Maybe this kind of conflict only makes sense because it's in a mixed Eastern/Western context, an Asian-American student and his first-generation immigrant father.

The last time I blogged on Asian child-rearing was when I described a book club response to Adeline Yeh Mah's, Falling Leaves: The Memoir of an Unwanted Chinese Daughter. The book is the story of a Chinese woman who suffers life-long disconnection and rejection from her step-mother. Just as in the television example above, the author sees her conflict from a Western perspective, as a woman who was raised in China, but received her higher education in England, and chooses to adopt Western ways of thinking.

I remember reading a translation of an old Chinese play in a college world literature class, The Peach Blossom Fan written in the 1600s. It's about a couple in love who were married, and then tragically separated from each other for several years. Day after day they pine for each other. Then, finally, fate sees fit to bring them near each other, and just as they are about to be reunited, a Daoist teacher encourages them to give up their passion, forgo the union, and go their separate ways, to live lives of meditation and moderation. Surprisingly, they do exactly as he advises. In class, my professor laughed at our response, explaining that Americans usually find the story appalling or confusing, while to the intended audience, the ending is very satisfying, because to them it would be clear from the beginning that the conflict that needed to be resolved was not the lovers' separation, but their childish response to the separation, their reckless emotional state. (This reminds me of the contrast between how I used to read Romeo and Juliet, and how I read it now. When I was young, it was a poignant story about love so true that without the one you love, life is not worth living. But now I see it as a cautionary tale about what happens when teens get too carried away with infatuation.)

The point is, your own culture's values are not as universal as you think. Most Americans and other Westerners are in constant search of deep emotional connectivity, affection, and individuality. People of other cultures live life with completely different objectives.

Next time I see Sunny, I think I will ask, "What, for you, is the purpose of life?" I can't wait to hear her perspective.

Here's the socio-cultural backdrop for the scene: Justin and Sunny are both students in the physics graduate program at University of Utah. Justin and I (and Lydia) are white with mostly British heritage, our families have been American for many generations. Sunny and her parents are of Chinese heritage, although she was born and raised in Malaysia. She came to the states on her own last year when she started the graduate program at UU. Her first language is English, which she says is typical for those who grow up in "British-occupied" Malaysia.

We were chatting about Meyer's Brigg's personality types, when Lydia became the topic of conversion. Here's my best attempt at paraphrase:

"You can tell there's something different about her," said Sunny.

"You mean, because she's so extroverted?" I said.

"Well," Sunny continued, "she has a kind of victorian grace, but she let's you know that she's in charge. She reminds me of Queen Elizabeth." People often comment on Lydia's character. She's a friendly, bossy, charming, loud, wide-eyed, unbridled, curious busy-body who happens to say "thank you" when you hand something to her.

Sunny added more, "Lydia really fills up the room." I mentally reflected on how Lydia had just filled a large musical instrument store with all her Lydia-ness. She ran here and there, squealing like a little pig while I chased her, calling, "No, no, no, don't touch the harps!" "Pick up those reeds and put them back, Baby!" "Okay, fine, you can play that piano, but not with your feet, please!"

"Asian babies are much different" Sunny said a moment later. "They are very passive." I immediately tried to think of an exception, but I couldn't.

"I'm going through my head trying to picture the Asian babies I know," I said, "And all of them are like what you're saying, very reserved. Why is that, do you think? I mean, in your opinion, would you say that's genetics or upbringing?"

"It's because of the way they are raised," she replied.

"What do Asian parents do differently?" I asked.

"They purposely disconnect themselves from their children. They don't show affection. They don't interact much with them, even when they are babies. They don't even use baby-talk with them, they speak to them like they're adults." She went into more detail, but this was the essence. I had heard of Asian parents demanding great discipline and excellence from their children, and the strain this must inevitably put on the child-parent relationship, but I had never imagined these scenarios within the context of growing up sans affection, and with limited interaction.

I was overcome by how backward it sounded to me. How can an entire culture of people, generation after generation, live without familial closeness and emotional dependence? The idea was contrary to everything I believe and value about life. I wanted to know what Sunny thought about it.

"When you have children some day," I asked, "do you think you will raise them the same way you were brought up, or will you do it the way Americans do?"

She hesitated, thinking about it, then answered, "I think I will do it the Asian way . . . Yes, I will."

I was surprised, so of course I had to ask (trying to give up my bias), "And why do you want to do it that way? What would you say are the benefits?"

I loved Sunny's response. Without a hint of defensiveness, she replied, "The way my parents raised me taught me independence. Even as a child, I knew that I could take care of myself, that I didn't need them--this was a great gift that they gave me." She also explained that while her parents didn't put an emphasis on closeness, they were not neglectful. "To them, being a good parent was about being responsible, following through on your duty." She spoke of them with consistent admiration.

I asked her if she felt like her parents loved her. She said that the first time she really felt their love, was last year when she was new in the U.S. and was in a situation of desperation. "I just asked for their help, and they were so generous--I couldn't believe it."

I thought of an episode of Glee I had seen in which an student begs his father to accept his choice to become a professional dancer. The student expresses a longing for his father's approval and love. He suddenly becomes aware of his father's disconnectedness, and finds it tragic. Maybe this kind of conflict only makes sense because it's in a mixed Eastern/Western context, an Asian-American student and his first-generation immigrant father.

The last time I blogged on Asian child-rearing was when I described a book club response to Adeline Yeh Mah's, Falling Leaves: The Memoir of an Unwanted Chinese Daughter. The book is the story of a Chinese woman who suffers life-long disconnection and rejection from her step-mother. Just as in the television example above, the author sees her conflict from a Western perspective, as a woman who was raised in China, but received her higher education in England, and chooses to adopt Western ways of thinking.

I remember reading a translation of an old Chinese play in a college world literature class, The Peach Blossom Fan written in the 1600s. It's about a couple in love who were married, and then tragically separated from each other for several years. Day after day they pine for each other. Then, finally, fate sees fit to bring them near each other, and just as they are about to be reunited, a Daoist teacher encourages them to give up their passion, forgo the union, and go their separate ways, to live lives of meditation and moderation. Surprisingly, they do exactly as he advises. In class, my professor laughed at our response, explaining that Americans usually find the story appalling or confusing, while to the intended audience, the ending is very satisfying, because to them it would be clear from the beginning that the conflict that needed to be resolved was not the lovers' separation, but their childish response to the separation, their reckless emotional state. (This reminds me of the contrast between how I used to read Romeo and Juliet, and how I read it now. When I was young, it was a poignant story about love so true that without the one you love, life is not worth living. But now I see it as a cautionary tale about what happens when teens get too carried away with infatuation.)

The point is, your own culture's values are not as universal as you think. Most Americans and other Westerners are in constant search of deep emotional connectivity, affection, and individuality. People of other cultures live life with completely different objectives.

Next time I see Sunny, I think I will ask, "What, for you, is the purpose of life?" I can't wait to hear her perspective.

Wednesday, November 7, 2012

My survey: Finding out what immigrants think of Utah's new Guest-Worker Program (Part 1)

Utah's Guest Worker Program (Utah Immigration Enforcement and Accountability Act, formerly HB116) stayed intact

through this spring's legislative session, despite some legislators'

threats to repeal it. If things go as planned, the program will start

granting state-approved legal work status to undocumented immigrants living in Utah next summer, 2013. Personally, I have high-hopes that this bi-partisan experiment will function successfully. But I have some questions about

how things will pan out.

What

percentage of undocumented immigrants will actually apply to enter the

program? Is there a broad awareness of the program among Utah's

undocumented immigrants? What are immigrants saying about it? Are there

aspects of the program (in it's current form) that will deter many

undocumented immigrants from getting on board? (I'm particularly

interested to know if undocumented immigrants will be daunted by the

high application fee ($1,500-$2,000), or if many are concerned about the

fact that if the legislation changed after implementation of the

program, the state would suddenly have record of thousands

of immigrants without legal status.) To what extent does/will the

immigrant community trust this program?

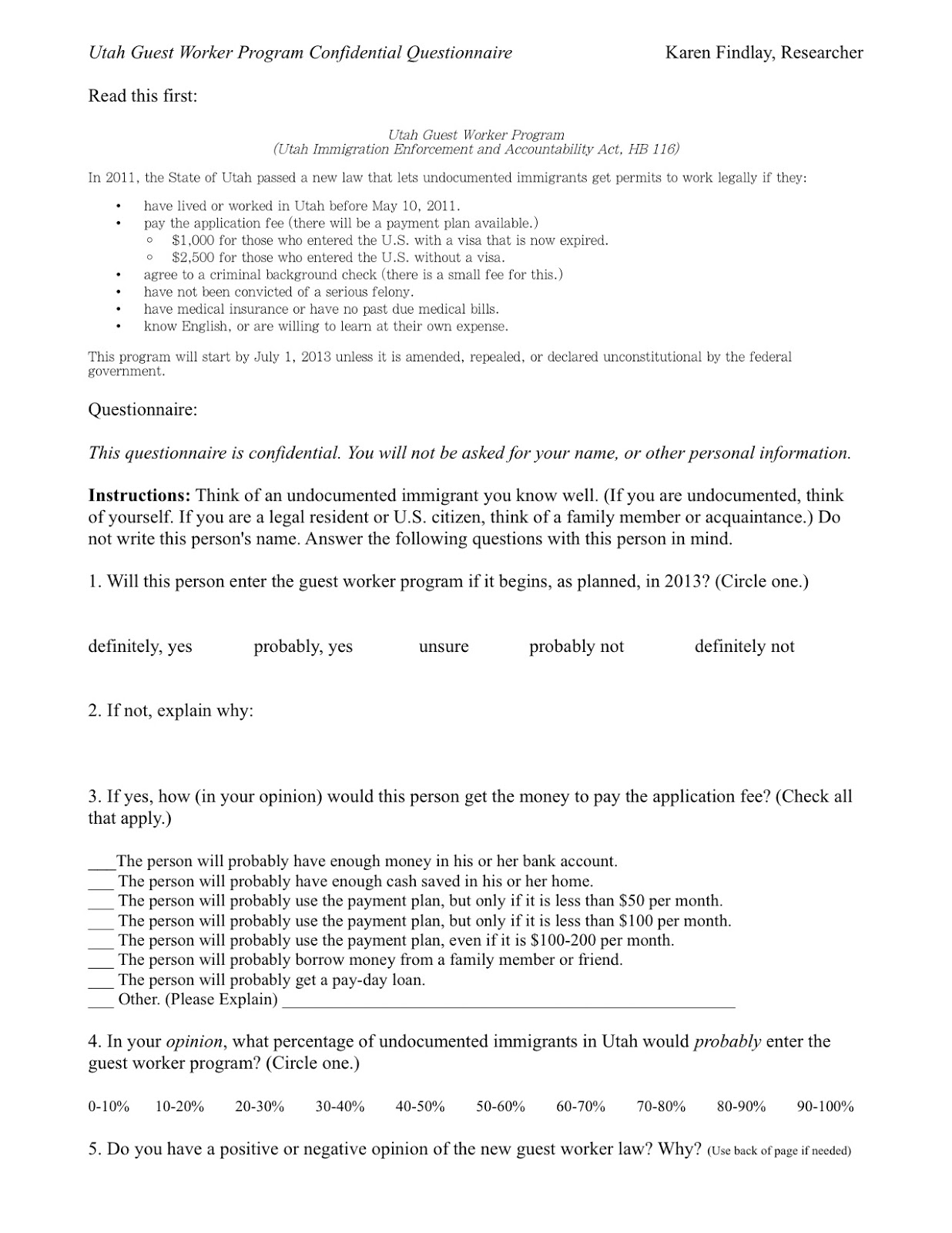

At any rate, I decided to put together a survey in which I ask immigrants (both documented and undocumented) for their opinions of the program, and their predictions of how well it will succeed without asking leading questions. To the left is an image file of the survey I came up with. (Click here to view or download document from Scribd.com). Thanks to some thoughtful friends, I have translations of the survey in Spanish, Japanese, Traditional and Simplified Mandarin Chinese, and Vietnamese.

My goal is to administer the questionnaire to about 200 immigrants. (I see this as more of a pilot study than a quantitative research project). So far, I've had only 47 participants.

Late spring this year (2012), I attended the Rose Park Community Festival, where I wheeled a toddler-bearing stroller, and wielded a couple of survey-bearing clipboards. I walked around for the last hour of the festival asking strangers if they were immigrants and if they'd be willing to complete a confidential survey. When I got home, I was amazed to discover that I'd only surveyed 10 individuals! That's when I decided I'd need to start searching for ELL classrooms.

Guadalupe School is a small community education center on Salt Lake's west side. They offer a toddler-preschool early education program, an elementary charter school program, and an adult English Language Learning program in addition to other community classes.

I visited the school twice last month to conduct my study with two classrooms of their adult ELL students. From the Monday night classroom, I administered 16 surveys, and from the Wednesday night classroom, 21. In both classes, the preferred language in which to take the survey was Spanish for every student. I was surprised how many students had questions about the Guest Worker Program before completing the survey. Maybe I should add, "Had you heard of this new guest worker program before today?" as an additional survey question.

|

| Utah Guest Worker Program Survey for Immigrants |

At any rate, I decided to put together a survey in which I ask immigrants (both documented and undocumented) for their opinions of the program, and their predictions of how well it will succeed without asking leading questions. To the left is an image file of the survey I came up with. (Click here to view or download document from Scribd.com). Thanks to some thoughtful friends, I have translations of the survey in Spanish, Japanese, Traditional and Simplified Mandarin Chinese, and Vietnamese.

My goal is to administer the questionnaire to about 200 immigrants. (I see this as more of a pilot study than a quantitative research project). So far, I've had only 47 participants.

Late spring this year (2012), I attended the Rose Park Community Festival, where I wheeled a toddler-bearing stroller, and wielded a couple of survey-bearing clipboards. I walked around for the last hour of the festival asking strangers if they were immigrants and if they'd be willing to complete a confidential survey. When I got home, I was amazed to discover that I'd only surveyed 10 individuals! That's when I decided I'd need to start searching for ELL classrooms.

|

| Guadalupe School |

I visited the school twice last month to conduct my study with two classrooms of their adult ELL students. From the Monday night classroom, I administered 16 surveys, and from the Wednesday night classroom, 21. In both classes, the preferred language in which to take the survey was Spanish for every student. I was surprised how many students had questions about the Guest Worker Program before completing the survey. Maybe I should add, "Had you heard of this new guest worker program before today?" as an additional survey question.

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Book Review: "Mormon Polygamy, A History" by Richard S. Van Wagoner

This is the second installment in a Utah History book review series on 19th Century Mormon Polygamy. (For readers less familiar with Mormon history, it's important to note that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints ended the church-sanctioned practice of polygamy in 1890.)A few weeks ago (Oct. 6, 2012), I drove through the Mormon pilgrimage to Salt Lake City's Temple Square. My sister and her boyfriend had tickets to the Saturday afternoon session of the LDS Church's biannual General Conference, I dropped them off, and then headed home to watch the conference live on LDS.org. Hoards of Latter-Day Saints filled the cross-walks and sidewalks that afternoon, and as ever, these Sunday-best dressed pedestrians tried to avoid the pamphlets and shouts of antagonists on the lawn outside the temple gates. You know what I mean, the folks wielding signs with slogans like, "Joseph Smith was a Satanist," or "The Book of Mormon is a fraud!"

The anti-Mormon movement is a old phenomenon, it started almost as soon as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints was founded. Because of the enthusiastic complaints of early 19th Century excommunicants from the Church, history is rife with reports of LDS scandal and hypocrisy, easy fodder for anti-Mormon literature. The question is, how is any student of history to know truth from fiction?

History may not be as precise a science as physics or chemistry, but real historians are trained to analyze and evaluate historical evidence. For example, they may present several accounts of an event, and emphasize that a first-hand account is more reliable than a second-hand account, a story told the day it occurred is more reliable than one told in retrospect several decades afterward, and the version expressed by an outsider is perhaps less-informed, but more objective than the versions told by those with strong positive or negative bias.

That's what I like about Richard S. Van Wagoner's Mormon Polygamy, A History. In the body and end-notes of his book, Van Wagoner frequently offers analysis of the sources he presents based on the criteria I've described in the previous paragraph. He also adds scholarly objectivity by exposing both sides of the story throughout the book.

I particularly love the chapter, "Women in Polygamy," in which Van Wagoner quotes many 19th Century polygamous women, allowing them to share their own reflections about polygamous life. In this chapter, Van Wagoner argues that life in polygamy was not the "harem, dominated by lascivious males" portrayed by journalists in the late 1800s, and neither was it always the happy ideal plural wives felt compelled to report in public (Mormon Polygamy, A History, pages 89-104). He uses, among other well-chosen quotations, this fascinating statement by Zina D. Jacobs Smith Young, plural wife first to Joseph Smith and then to Brigham Young, and the third General President of the Relief Society:

Much of the unhappiness found in polygamous families is due to the women themselves. They expect too much from the husband, and because they do not get it, or see a little attention bestowed upon one of the other wives, they become sullen and morose, and permit their ill-temper to finally find vent . . . a successful polygamous wife must regard her husband with indifference, and with no other feeling than that of reverence, for love we regard as a false sentiment; a feeling which should have no existence in polygamy (New York World, November 19, 1869; quoted in Mormon Polygamy, A History, page 101).More About Van Wagoner

|

| Richard Van Wagoner |

It's important for readers to know that Van Wagoner is not without his own bias. He was a fifth-generation, life-long Mormon, and BYU graduate. But, personally, that's one of the things I loved about the book--I'm always curious about how Mormon scholars, sifting through thousands of positive and negative accounts of LDS history, come through it all without loss of faith. Although I've said here that Van Wagoner considers both points of view in his book, he doesn't treat them equally. Overall he argues that a holistic study of Joseph Smith's perspective and experiences, leads readers to see him as a man of ethical leadership and moral integrity. For example, Van Wagoner first reveals statements made in the 1830s and 1840s in which Joseph (already married to Emma Smith) was accused of indecent proposals and extra-marital sexual relationships. Then, in addition to showing the anti-Mormon bias that accompany some of these stories, Van Wagoner says:

Accounts such as these have led some historians to conclude that Joseph Smith was licentious. But others have countered that these stories merely indicate his [early] involvement in a heaven-sanctioned system of polygamy, influenced by Old Testament models (Mormon Polygamy, A History, page 5).Note: While neither the Church nor Joseph Smith went public about polygamy until the publication of the 12 July 1843 revelation on Celestial Marriage (D&C 132), the first widely recognized plural marriage of Joseph Smith was to Louisa Beaman in 1841. There are also several reports that Joseph Smith was teaching the spiritual principle of plurality of wives to some of his friends in church leadership as early as 1831 (Mormon Polygamy, A History, page 3).

What other LDS scholars say about Van Wagoner

In my search to know what other faithful Mormon historians have said about Van Wagoner's work, I happened upon a couple of interesting articles published on scholarly websites associated with Brigham Young University.

The first article I found in BYU Studies, a quarterly print and electronic journal. The review is written by another famed LDS historian, emeritus BYU professor, Thomas G. Alexander. Alexander calls Mormon Polygamy, A History, a "generally accurate summary of previous published studies." He's pleased that Van Wagoner's work agrees with Joseph Smith's own interpretations of the origins of Mormon plural marriage. He commends Van Wagoner on some of his data interpretations--like admitting that findings on the nature of Joseph Smith's relationship with Fanny Alger are inconclusive. Alexander also points out something that Van Wagoner missed, a piece of the Fanny Alger story that couldn't possibly be true when time and place are fully considered:

He suggests that Van Wagoner's work is a step above the work of Mormon authors who, in defense of polygamy, over-do it with "outmoded and indefensible rationalizations," such as spreading the idea that plural marriage was limited to only 2 or 3 percent of Mormon marriages, or that polygamy was necessary to provide husbands for excess females while there is significant historical and sociological evidence that these ideas are just not true. Alexander also calls Van Wagoner's findings, "moderate," which I assume is a compliment.He [Van Wagoner] cites an alleged interview in the St. George Temple between an unnamed person and Heber C. Kimball, who is said to have introduced Fanny's brother John as the brother of Joseph Smith's first plural wife. This would have been an extraordinary feat since the St. George Temple was not dedicated until 1877 and Heber C. Kimball died in 1868. (Thomas G. Alexander's Review of Mormon Polygamy, A History; BYU Studies)

Thomas G. Alexander

When Alexander calls the book, "generally true," I take that to mean, it's worth reading, but take it with a grain of salt. His overall opinion of the book seems to be that it's nothing new, nothing special, just a relatively mature compilation of stuff that's already been published. (Of course all of this is old news to the Mormon history world, Van Wagoner's second edition of the book was published in 1989.) Alexander emphasizes that there remain many unanswered questions about 19th Century Mormon Polygamy.

The second article I want to mention is a Maxwell Institute publication. It's a mostly negative review of Van Wagoner's award-winning book on early LDS Church leader, Sidney Rigdon, Sidney Rigdon: A Portrait of Religious Excess. (They didn't have a review on Mormon Polygamy, A History.) So, although this review has nothing to do with Van Wagoner's research on Mormon polygamy, I'm passing this along, because it was helpful to me to see what the Maxwell Institute scholars have said about Van Wagoner.

In this Maxwell Institute review, the authors praise Van Wagoner for arguing that "Rigdon played a crucial role in the development of early Mormonism and that his contribution was diminished in the wake of his unsuccessful bid to shoulder Mormon leadership after the martyrdom of Joseph Smith." However, they disagree with what seems to have been Van Wagoner's big scholarly project, posthumously diagnosing Rigdon with bipolar disorder. Meanwhile, it seems the reviewers' main concern with Van Wagoner's writing is this:

He intends to expose the "warts and double chins of religious leaders" and "warns all of us that we must ultimately think for ourselves rather than surrender decision-making to others, especially to those who dictate what God would have us do" (Sidney Rigdon: A Portrait of Religious Excess, pp. x, 457—58). In this way Van Wagoner casts Sidney Rigdon as an object lesson calculated to censure modern Mormons for what his related Journal of Mormon History essay calls "group gullibility" (Van Wagoner's Sidney Rigdon: A Portrait of Biographical Excess.)I laughed when I read that statement. After reading his polygamy research, Van Wagoner strikes me as a skeptic with resilient faith, whereas these Maxwell Institute reviewers seem (to me) to have exaggerated him as a dissident. But what do I know? I haven't read Van Wagoner's work on Sidney Rigdon. I'm just a lady who who had a very positive reaction to Mormon Polygamy, A History.

Note: The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship is a branch of Brigham Young University that issues research fellowships, produces lecture series and publishes Mormon studies research in journal and book form. The institute is operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

My critique of the book

Although I mentioned (above) my admiration for Van Wagoner's evaluation of his sources, I must criticize him for not doing so consistently. There were a great many sources for controversial accounts that he does not evaluate. For example, In the chapter "Women in Polygamy," he frequently uses quotations from a magazine or newspaper called, "The Anti-Polygamy Standard," but he does not offer background information on the origin or nature of the publication. He also fails to comment on how the publication's presumably strong anti-polygamy bias might affect the legitimacy of the quotations found in it (journalists exaggerating the truth to prove a point, yellow journalism, etc.)

I also disliked the book's unclear parenthetical citation format (more like a non-format.) I'm not saying all historical books should be in MLA, APA or Chicago style (Did those exist in the '80s?), but I am saying that they should have some consistent manner of documentation that clearly leads the reader from the parenthesis to its correlated reference in the bibliography. Some of the parenthetical citations in Van Wagoner's book contain abbreviations, or other shortened, confusing references. I often had to skim through the paragraph again in order to find all the clues I needed to find the source in the bibliography. Additionally, there are some sources (like newspaper publications and personal letters) for which there are no bibliographical entries at all. Van Wagoner gives the date, the name of the publication or recipient, but nothing more. This is extremely problematic.

Overall, I recommend this book for critical thinkers. Van Wagoner presents historical accounts, reminds readers to question sources, and while he makes clear his own interpretations, he leaves room for the reader to draw his or her own conclusions. As far as my own conclusions are concerned, I have to agree with Thomas Alexander, there are many questions about the beginnings of Mormon polygamy that historians have not yet adequately answered.

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

Book Review: "More Wives Than One" by Kathryn M. Daynes

For years I've had in mind the goal of getting my hands on a few good books about pre-1890, Utah Mormon pioneer polygamy. (1890 is the year The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints formally discontinued the practice of plural marriages.) I'm a faithful Mormon myself, so I wasn't interested in anything with an antagonistic bias toward the Church. I also wanted something objective and academic, rather than a book of faith-promoting tales. Eventually, I decided what I wanted was a publication critically acclaimed by both LDS and non-LDS scholars.

Over the past few months I've discovered and read several books that fit the bill! This blog post is the first in my series of reviews of scholarly books on Utah Mormon polygamy.

Here's today's recommended read:

More Wives Than One: Transformation of the Mormon Marriage System 1840-1910

by Kathryn M. Daynes, University of Illinois Press, 2001

Daynes is a professor of history at Brigham Young University, and served as president of the Mormon History Association 2008-2009. This book started as Daynes's graduate dissertation, funded by a grant from Indiana University. My favorite thing about the book is its meticulous primary and secondary source citation. More Wives Than One contains 816 end notes, and a 14-page-long selected bibliography. It's a fairly short read, only 214 pages, if you don't count the appendix.

The first chapter of the book is an excellent summary of the beginnings of polygamy among the Latter-Day Saints in Kirtland (Ohio), and Nauvoo (Illinois). The remainder of the book is a historical and demographic analysis of one specific community, the city of Manti, Utah from its settlement in 1849 to 1910. Daynes goes into a detailed study of the plural marriage customs, complex doctrines, state marriage laws and

other cultural phenomena that serve to thoroughly illustrate the nature

of Mormon society in 19th Century Utah. She then presents quantitative sociological data gathered from marriage records, censuses, and other historical documents pertaining to Manti, Utah. With this data she analyzes

For those who don't mind the academic lingo, it's an awesome read!

Over the past few months I've discovered and read several books that fit the bill! This blog post is the first in my series of reviews of scholarly books on Utah Mormon polygamy.

Here's today's recommended read:

More Wives Than One: Transformation of the Mormon Marriage System 1840-1910

by Kathryn M. Daynes, University of Illinois Press, 2001

|

| Kathryn M. Daynes |

|

| More Wives Than One cover image |

- The Marriage Market (Ch.5) (Daynes surveys the ratios of men to women over time. She also discusses the departure of unmarried men from Manti in search of work and marriage prospects, and the influx of new immigrants, both male and female.)

- Women Who Became Plural Wives (Ch. 6). (In this chapter, Daynes shares demographic information about polygamous women across time. This info set includes facts about common ages for new brides, the difference in social status between first wives and plural wives, among other family life details.)

- Economics and Plural Marriage (Ch. 7) (Here, Daynes concludes that polygamy actually solved some societal economic problems in Manti. For example, wealthy men commonly took women from lower-class families as plural wives, which meant a pattern of wealth redistribution from the rich to the poor.)

- Civil and Ecclesiastical Divorce (Ch. 8) and

- Incidence of Divorce and Remarriage (Ch. 8-9)

For those who don't mind the academic lingo, it's an awesome read!

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

Spring/Summer Sabbatical 2012

Dear Readers,

Just thought I'd let you know I'm taking a sabbatical from blogging April-August 2012 in order to complete some larger research and writing projects this summer. I'll be working on a biographical play about Utah pioneer, Wilford Woodruff; a quantitative study on Utah immigrants' response to the state guest worker program that will start in 2013; and a qualitative study on race and violence in secondary public schools in the Intermountain West region.

Karen

Just thought I'd let you know I'm taking a sabbatical from blogging April-August 2012 in order to complete some larger research and writing projects this summer. I'll be working on a biographical play about Utah pioneer, Wilford Woodruff; a quantitative study on Utah immigrants' response to the state guest worker program that will start in 2013; and a qualitative study on race and violence in secondary public schools in the Intermountain West region.

Karen

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)